Net Working Capital is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of M&A deal structures—not only in terms of its definition but also its purpose. Net Working Capital Targets are a common structure included in most middle-market transactions.

“Net Working Capital” is commonly defined as Current Assets less Current Liabilities. However, specific Current Assets and Current Liabilities may be excluded from the sale, which can impact the final NWC calculation.

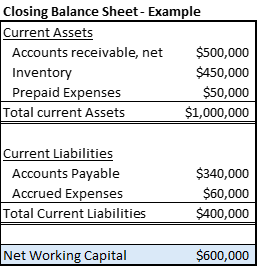

To explore Net Working Capital a little further, we will show an example using the closing Balance Sheet below.

In the partial Balance Sheet above, let’s assume that the buyer and seller agreed on a Net Working Capital Target of $500,000. As shown in the example, the actual Net Working Capital amount delivered at closing was $600,000. Because the seller delivered excess Net Working Capital of $100,000, the Total Purchase Price would be adjusted upward by $100,000.

A Net Working Capital Target ensures fairness for both buyers and sellers by:

- Providing the buyer with adequate working capital

- Compensating the seller for excess working capital

Why Is the Net Working Capital Target Set Before Closing?

The NWC Target is calculated before closing to account for fluctuations in the business's financial performance leading up to the sale.

- If the business performs exceptionally well, resulting in higher-than-expected NWC, the seller is compensated for the additional value.

- If the business underperforms, leading to lower-than-expected NWC, the buyer is protected by receiving a discounted purchase price.

Using a Net Working Capital Target as part of the Total Purchase Price provides a fair and structured approach to ensuring that both parties are protected. It helps buyers maintain business continuity post-acquisition while allowing sellers to be fairly compensated for any excess working capital delivered at closing.